The dive: searching for deep ocean plastics in the Puerto Rico Trench

Editor’s note

JCVI Staff Scientist Erin Garza, Ph.D., was selected to embark on a unique research expedition aboard the HOV Alvin submersible, a crewed deep-ocean research vessel owned by the United States Navy and operated by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, that has brought explorers to extraordinary places for more than 50 years.

During the deep-sea expedition, she will be collecting plastic samples from the bottom of the ocean and analyzing them using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), metagenomics, and metatransciptomics to learn about potential microbial plastic degradation. These techniques will enable the identification of organisms that are present and what genes the organisms are actively expressing. These data will help provide an indication as to what metabolic pathways may be breaking down the plastic with the eventual goal of engineering microbes to safely and efficiently degrade plastics at large scale recycling facilities.

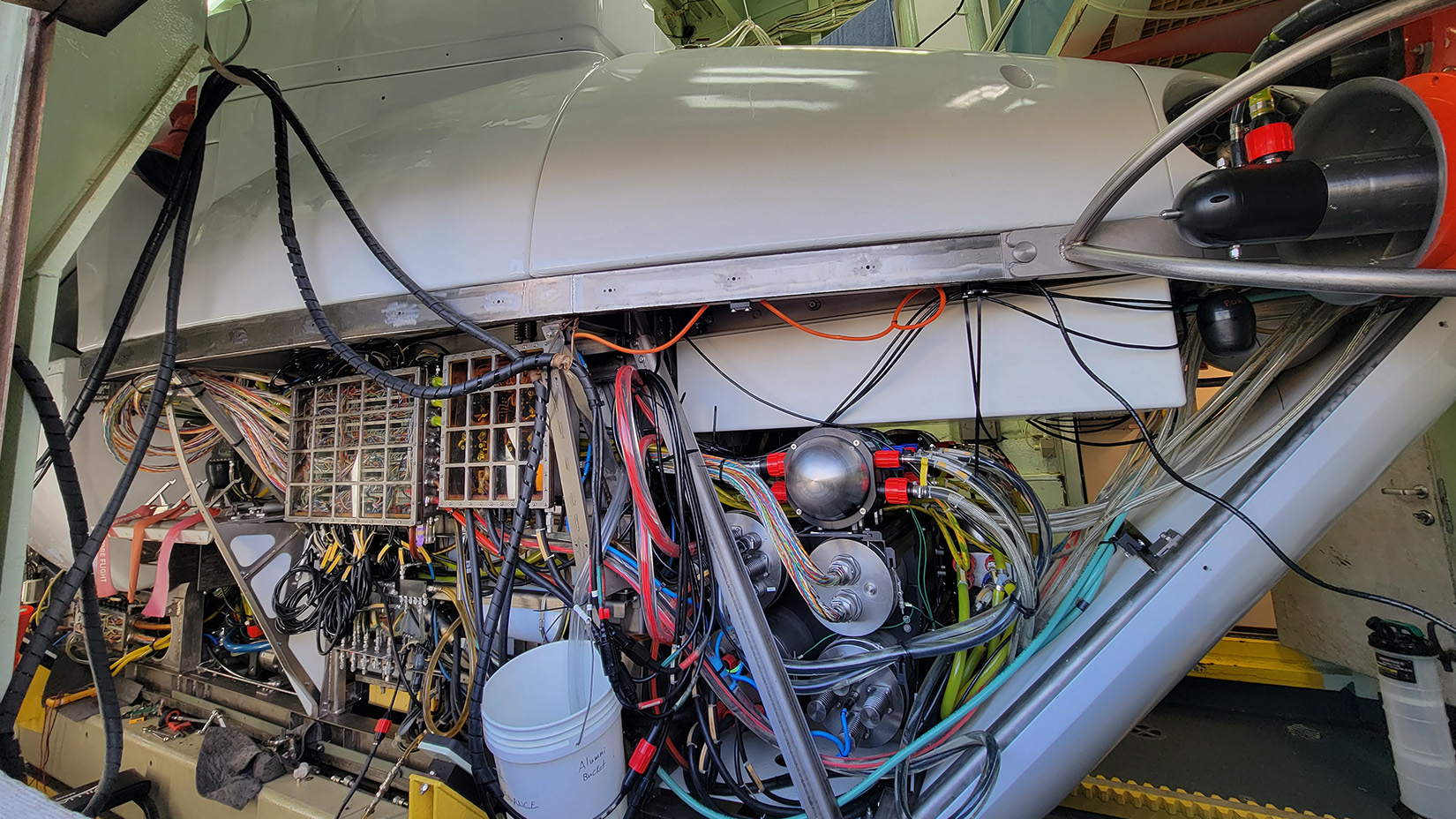

It is the day of my dive, and it is an early start for everyone. The Alvin engineers must be up at 5 AM so they can start prepping the sub, and the pilot and scientists must be ready on deck by 7:30 so the sub can be in the water by 8. I am so focused on what needs to be completed during the dive that I surprisingly don’t feel nervous at all. It seems like my brain has not yet registered that I am going to the bottom of the ocean because it is just too surreal.

I climb the stairs to the sub and wave goodbye to my colleagues. Once I’m in the sub, my fellow dive partner, Erik Cordes of Temple University, and I start turning on all the cameras and recording devices. Everything must be documented. There are even voice recorders that record what we say throughout the whole dive.

The entire launch flies by. I look up from my tablet to see the Alvin divers’ feet swim past the window as they unhook our tag lines. We are now free floating and start our descent to a target depth of 6,100 meters. I’m surprised at how quickly it becomes dark. There is very little light below 200 meters and with an average descent rate of 45 meters per minute we begin to enter the bathypelagic—or midnight zone—after only about 20 minutes. The pilot turns the exterior lights off and tells me to look out the window.

I immediately start to see an underwater firework show of lights. The bioluminescent organisms that live here light up the darkness like stars in a night sky, but it is too dark to see what is creating all this light, you only see the light itself. I will never know if the light I saw was the lure of an anglerfish or a clump of bioluminescent plankton.

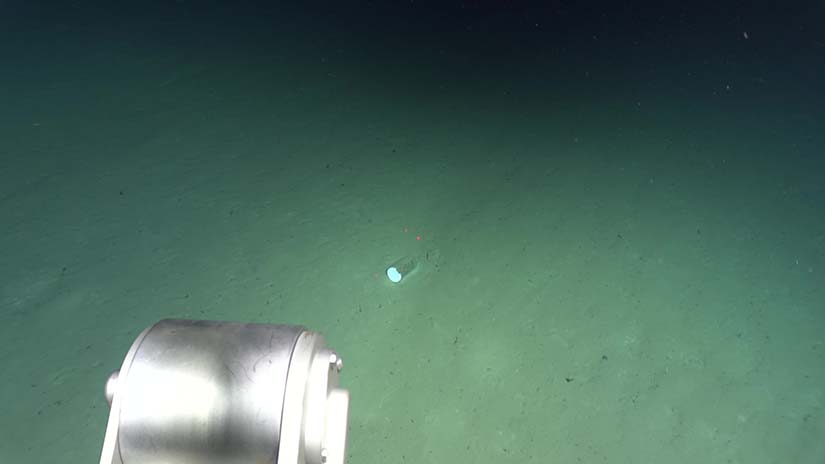

After about two and a half hours we reach the ocean bottom. The lights are turned back on, and I look upon a vast landscape of white sand spotted with the occasional brittle star or cusk-eel. It’s also snowing. Marine snow, made up of organic material that has sunk from the waters above, is a constant here. In a land almost completely devoid of color I feel like I’m drifting through a dream.

We spend the next few hours traversing the sea floor collecting samples. We find black coral, isopods carrying clumps of sargassum, crinoids or sea lilies, and a glass jar with a plastic lid. I’m particularly interested in the plastic lid because this will be our first plastic sample from almost 4 miles beneath the ocean surface. I’m excited to analyze the lid to determine what microbes are growing on it and whether any of them are degrading the plastic. This is amazing, I finally have my first deep sea sample.

We spend the rest of the dive collecting sediment cores and testing some chemical sensors before the ship radios down that it is time to return to the surface. We drop our weights and start our ascent. On the way up we eat lunch and ask our pilot, Bob Waters, about his life as an Alvin sub pilot. It turns out that Bob has been an Alvin pilot for over 10 years!

We emerge at the surface, and I can’t believe that the dive is over. It’s been about 9 hours, but it feels like only 2 or 3 have passed. The sub hatch is opened, and I am greeted with cheers as I step out on the deck. Not only was it a successful dive, but I am told that I now hold the record for deepest Alvin dive completed by a female at 6,110 meters. While I am elated and honored to hold this record it is one that I hope is quickly broken.

Now that the rush of the dive has passed it is time to collect my samples from the sub and start setting up my experiments. Then a new thought occurs. What if I just collected the first deep sea microbe capable of degrading plastic? This could change everything!